Introducing our William Tyndale statue, a masterpiece that combines historical significance, exquisite craftsmanship, and educational value. This statue is a tribute to the life and work of William Tyndale, a key figure in the Protestant Reformation. Tyndale's translation of the Bible into English laid the foundation for future generations of Christians.

The Biblical Heritage Exhibit exclusive statue, cast from a meticulously hand-sculpted original by Brandon Lane, captures the essence of Tyndale's commitment to his faith and his contributions to the religious landscape. It serves as a reminder of the power of faith and the importance of religious freedom. Perfect for educational institutions, churches, and history enthusiasts, this statue is a symbol of religious heritage and intellectual curiosity.

Product Dimensions: 5.75” wide x 5.75” deep x 16” high

Weight: 10.9 lb

Mamusse Wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God — more commonly known as the Algonquian Bible or the Eliot Indian Bible of 1663 — is widely recognized as the first Bible of any language to be printed on a printing press in North America, and the single largest printing endeavor of the early colonial period.

Created and produced by the dedicated team at the Biblical Heritage Exhibit, this facsimile reproduction is printed on opaque paper and bound in a rich brown distressed faux leather, adorned with detailed gold foil stamping.

As a non-profit educational organization, the Biblical Heritage Exhibit receives a majority of its funding through donations from individuals and organizations who desire to support our mission of educating the world about the history of the Bible.

We would be honored if you would help further our work by making a financial donation today!

If you wish to donate Bibles, artifacts, replicas, or other items, please contact us to discuss the details.

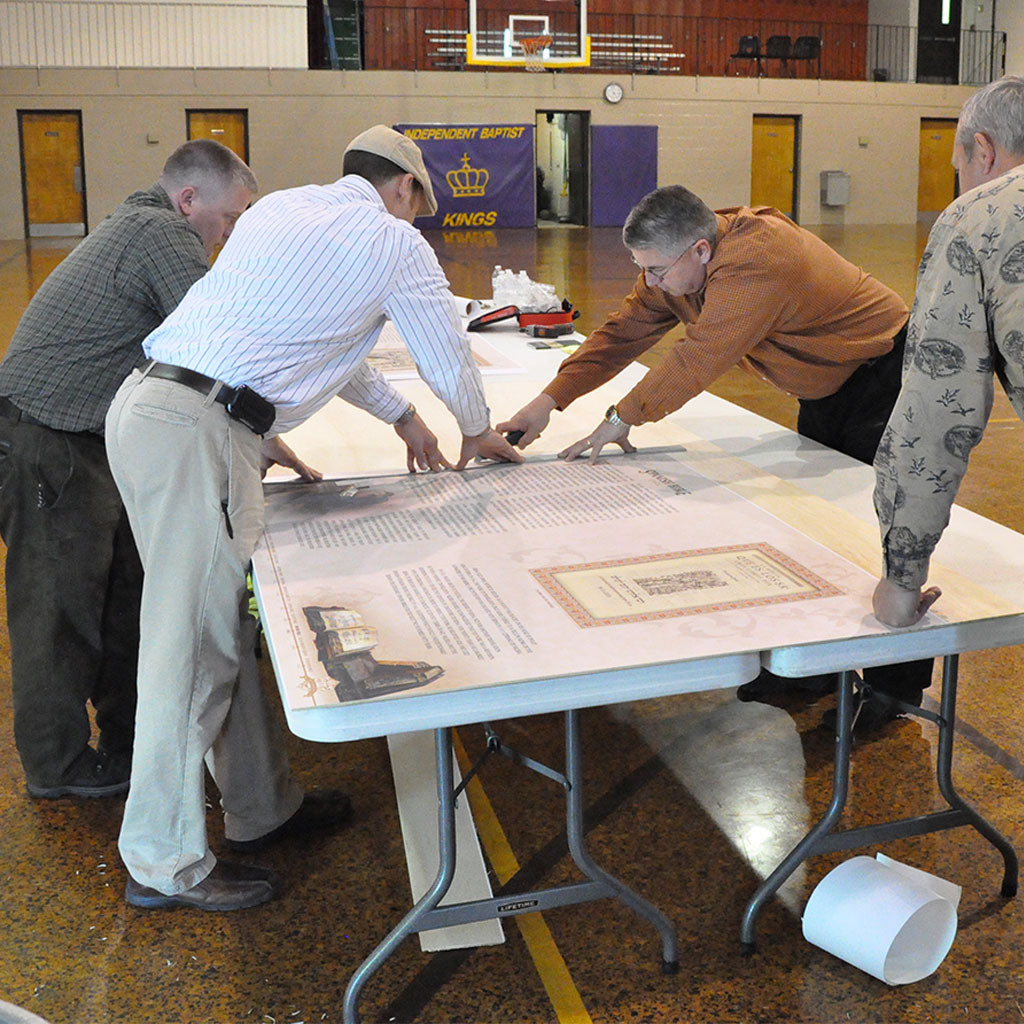

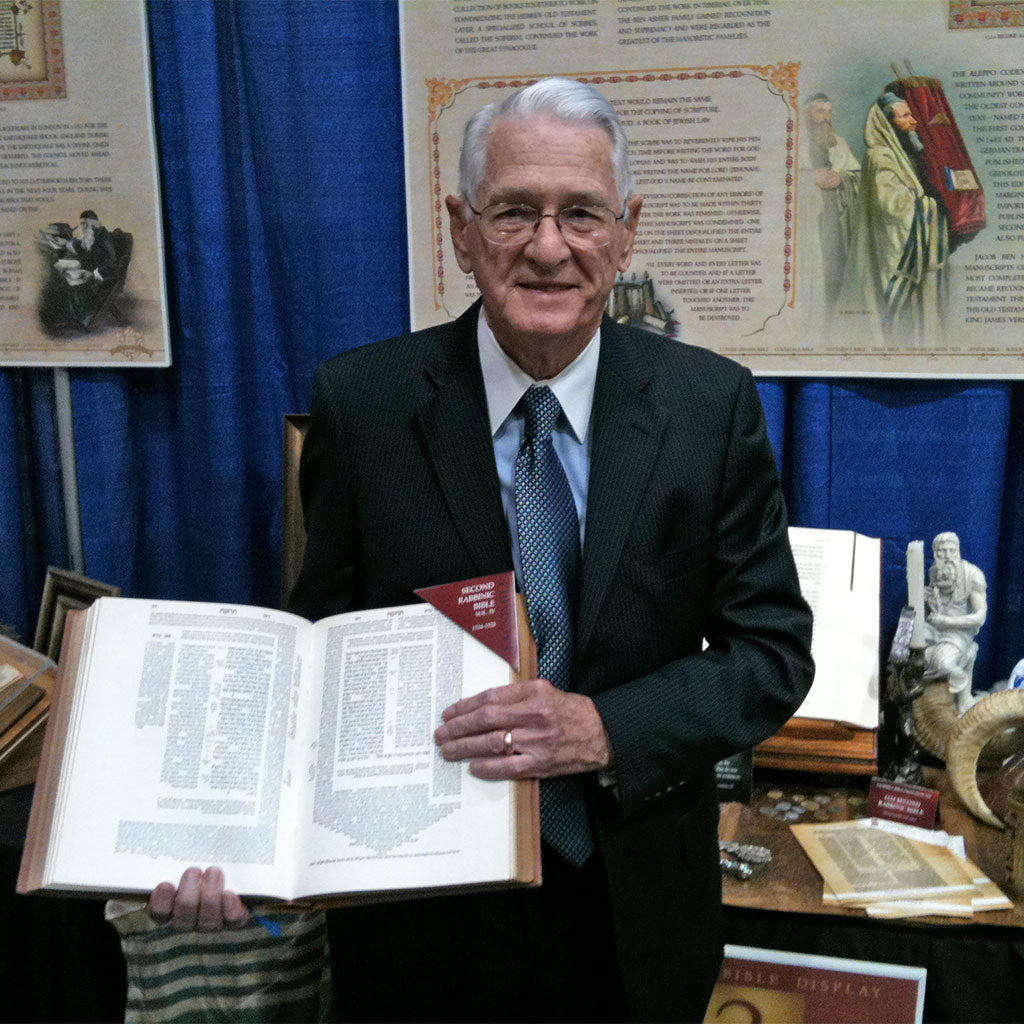

For over 10 years, the Biblical Heritage Exhibit family has strived towards our mission to teach the world the history of the Holy Word of God. Follow the link below to learn more about our efforts and collaborations that have made the Biblical Heritage Exhibit what it is today.